I am a non-tech guy — a definition that’s not unusual now.

We have tech and non-tech jobs, and I’ve settled into the notion that one’s about high-tech and the others don’t get much of tech.

Today’s story is about my search to discover the root cause of this division and how it contributed to my fear of technology.

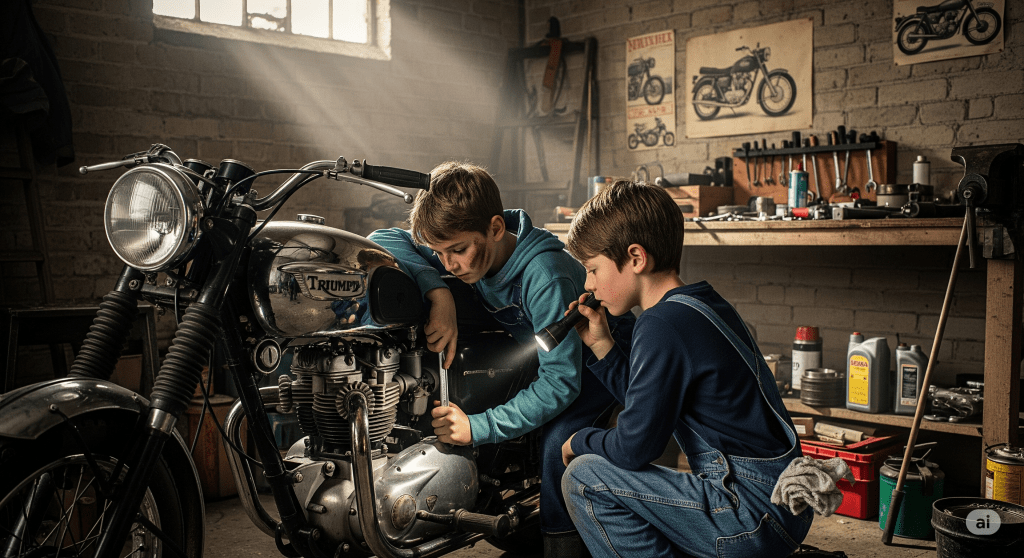

Growing up around machines

Since childhood, I have been discouraged from messing around with expensive housewares — be that a glass plate, tabletop fan, or a mixer grinder.

At home, every repair, installation, or upgrade required my dad’s approval. I was reminded of a clear hierarchy of who could tinker with ‘technology,’ and it was mostly elders — people who seemed to know how it worked.

A mixer grinder is surely a dangerous machine for kids, so let’s take the example of a motorcycle for our discussion.

The motorcycle analogy

Stage 1: My first motorcycle experience was atop the fuel tank of my cousin’s Hero Honda Splendor back in primary school.

I was allowed to sit and hold on to the handlebar. That was it. That was my exposure to that technology at the time. As I grew taller, I was allowed to sit on the bike but not start the engine. It was still a dangerous machine for a kid like me.

Stage 2: At higher secondary, I could roll on the bike from a slope, like a cycle, creating a pseudo-feeling of driving the machine.

Each of these experiences instilled a sense of fear and a strange respect towards the underlying technology of the motorcycle that was both expensive and out of reach for children at the time.

Stage 3: My first motorcycle ride was right after I gained my license. To my horror, it ended up in a crash, bending the crash guard and chipping the footpeg, not to mention the scratches on the handlebar and some dirt on our family’s brand-new bike.

That was enough for the technologist in me to hibernate indefinitely. Even when I tried to learn more, it kept providing me with expensive lessons that weren’t affordable for me at the time.

Common knowledge and wisdom

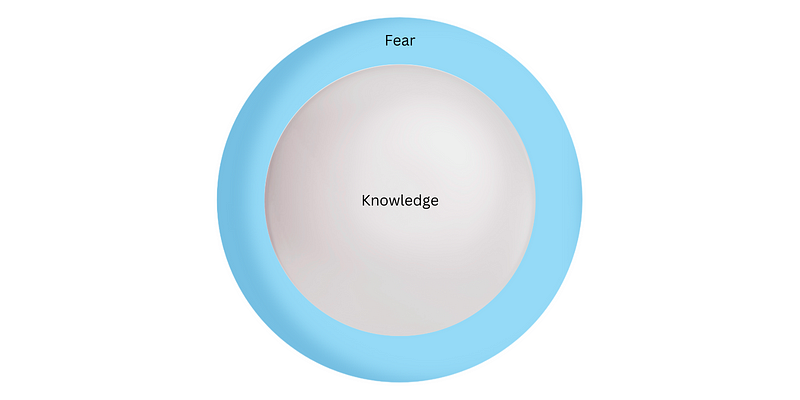

The above pattern is seen almost everywhere. At work, in relationships, and with topics related to unfamiliar tech. We either create our own limits, or we’re told of our limits — spheres of information from which we deduce what is common knowledge.

What I find peculiar is that this knowledge is constantly changing. And whenever it doesn’t, that’s where fear creeps in quite easily. So having a bigger sphere of experiential knowledge is beneficial to ward off fear.

Your sphere of experiential knowledge is inversely proportional to fear.

Even when I had my bike, there was always the hidden fear of what if my bike broke down somewhere remote, without mechanics, and how would I ride back home?

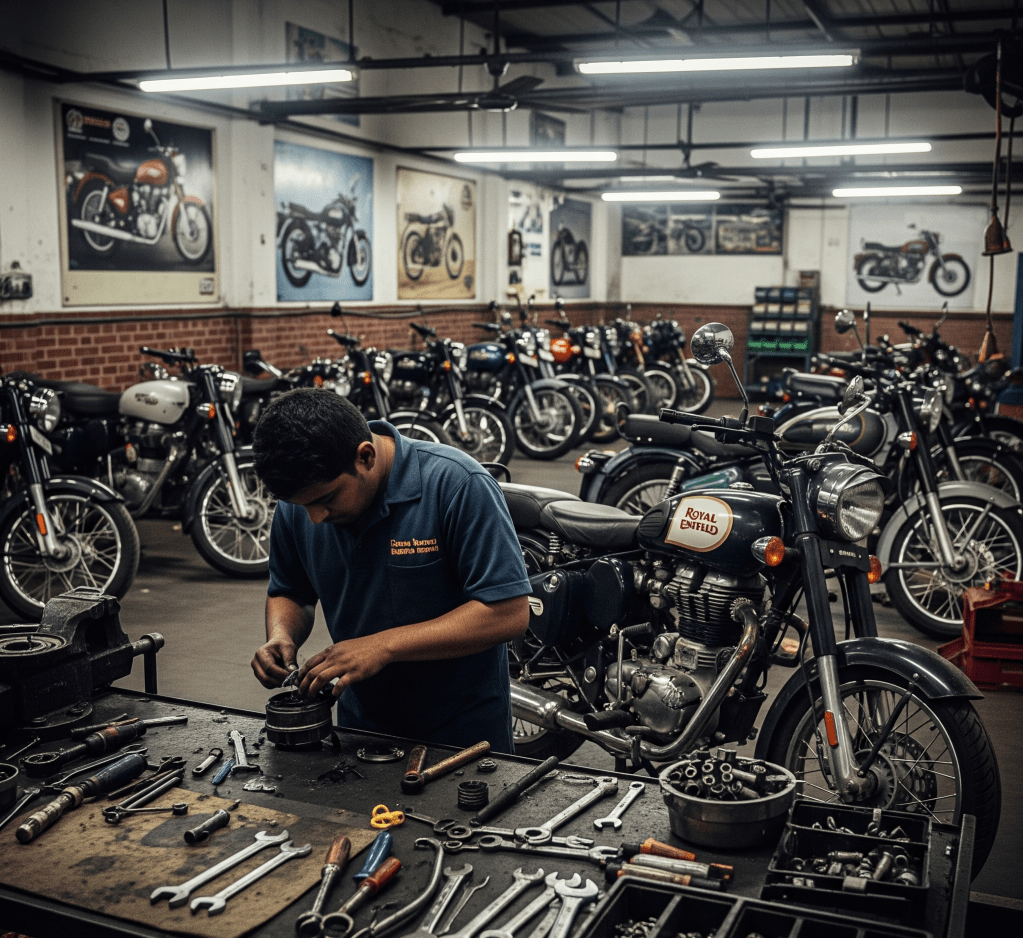

My first motorcycle was a Royal Enfield Thunderbird, notorious for its vibrations and loose chain. Being a mechanical engineering graduate, I was supposed to know every squeak and thud of the bike.

Here’s when my fear of getting judged translated into judging things prematurely.

I reasoned every inquiry with common knowledge, which didn’t solve anything. Unusual sounds from inside the engine were quickly refuted as tappet noise, which apparently couldn’t be solved, and loose chains were tightened too much to avoid chain noise, damaging the chain set in the process.

Moreover, I tried to be around mechanics to sound more credible. So when someone asked me a doubt about their machine, I would falsely quote the mechanics I knew and evade the subject abruptly.

No one asked if I had worked on a bike before. My closeness to mechanics implied it, solidifying this mindset of evading tech as much as possible.

Reasons behind my tech aversion

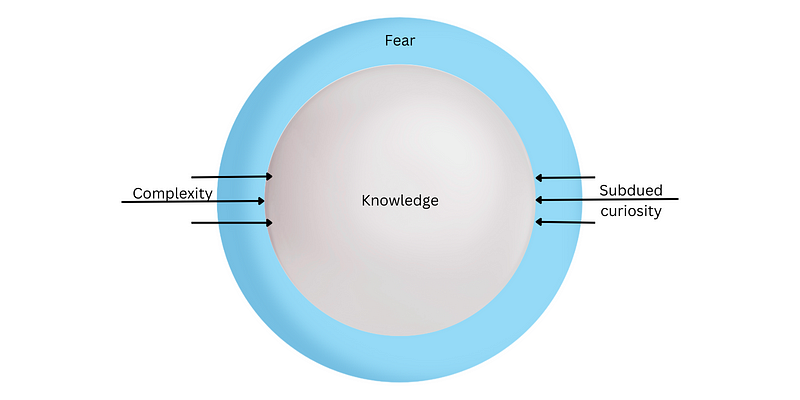

It took me years to finally realize what I was missing. Technology beyond my understanding made me uncomfortable. But hadn’t it always the complexity that puzzled me?

For context, I understand hinges perfectly. I know how it operates. I understand cycles fairly well. The underlying tech is simple and visible. I don’t have to use my substandard power of deduction to understand how it works.

So as they grow in number of parts or components that are too complex to grasp easily, I get scared and resort to short-term assumptions. But what this also does is solidify my assumptions into unquestioned truths if I don’t go deep into the tech.

Another aspect is how curious I can be with these machines. Unscrewing a toy or even a cycle is nothing our parents would consider a costly affair, nor would they think we are incapable of assembling it.

But when the underlying technology is kept hidden, it’s harder to have the same curiosity, especially when it’s designed not to be opened often. We are now immersed in technology that doesn’t ask for tinkering or maintenance.

It solidified my tech aversion. And since it was okay not to know the underlying tech to use it satisfactorily, curiosity quietly withdrew to the background, leaving a void naturally replaced by fear.

In short, complexity and subdued curiosity created my aversion to technology.

How to get over it?

It’s not easy, as common knowledge has its benefits. We use our intuitions and deductions to live our daily lives, and understanding tech is not always a key requirement to use it.

Two key things helped me generate a newfound humility toward complex technology.

Compassion and righteousness. Sounds strange? Let me explain.

The two pillars of wisdom

We are wired to consume information more than anything. It’s important for survival, but technology has greatly blurred the line between information and knowledge.

So when I hear someone say a bike produces 40 bhp, what knowledge am I supposed to gain from it? Have I ever felt a comparable power before? Does it mean it goes very fast?

This is where compassion comes into play. Understanding what the other guy knows and giving context to what it can be compared with is a great start. Also, technology is still a byproduct of someone’s curiosity, not machine-generated.

Therefore, the first step in explaining technology is to address the underlying fears of the listener.

So let’s not separate technology from the human experience.

Retracing to the 40 bhp example, how you use technology wisely has a lot to do with approaching technology the right way. That’s when righteousness comes into play.

A quick turn of the throttle may topple the rider from the bike. But that thought may not come to mind if you don’t know what turning the throttle feels like. So turning the throttle slowly has reason to exist, which becomes second nature and a part of our understanding.

This is how easily we can humanize technology and rekindle our curiosity to understand it better.

Our way forward

Somewhere along the way, man separated art from technology. While art is considered a thing of the heart and technology a result of logic, it’s easier to judge technology as lifeless and alien to a ‘humane’ experience.

With compassion and the right mindset, I’m ready to ask questions that not only take me beyond the curtain and see the underlying form of technology, but also gain an understanding of how to use it better, more wisely, and the way it is truly meant to be.

Leave a comment