Curiosity, scientific method, and an open mind.

Michael and I used to meet at his place every weekend to discuss AI.

I knew very little about it at the time, but he was humble enough to declare he also didn’t know much just to nurture curiosity as equals.

Every week, we’d discuss whatever we learned in AI. It was like studying a new subject like physics or math back in school.

After Aravind showed me how math could be fascinating with his vivid explanation of infinite series, I was hooked on knowing more about tech I didn’t fully understand.

This was just before the mass adoption of ChatGPT and definitely long before the Studio Ghiblification of everyone I know.

One evening, as I was discussing the book I was reading at the time—Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance—Michael introduced me to Claude, a new generative AI tool that could apparently create app prototypes in minutes.

I wasn’t sure how to ask the question of building a meditation timer. I fumbled and asked something mediocre, explaining my trouble of being unable to create an unintrusive alarm when my meditation ended.

To my surprise, it created a timer app with somewhat useful features and suggestions that actually worked.

This was my first real encounter with AI solving a real-world problem, and the first time I came to respect it as more than a mere answer-generating machine.

His bike breaks down a little later.

Understanding the Unknown

In the weeks that followed, I was introduced to Andrej Karpathy, a humble AI wizard who also happened to be an impressive online teacher, who taught me the basics of LLMs and what the GPT side of things really meant.

Thanks to Michael and Helen, my intrigue and enthusiasm to learn AI was heightened beyond measure.

Every unknown technology first instills fear in us. Like magic. Like fire.

If you’re honest, it gives way to curiosity that fuels the drive to ask questions to improve our understanding of it and the nature of things. This is a time-tested method from prehistory to the modern age, but only a few realize the pattern and leverage it for growth.

The ideas we stumbled upon were incidentally featured in the motorcycle maintenance book, where the author explains how we often consider unknown technology as the deathforce we must fight at all costs.

In the book, Robert explains how technology has alienated us from approaching it with curiosity. These logical machines work as though they don’t need us anymore, and we are rendered useless by their presence.

Our current fear of AI taking over jobs has a similar tone. Mankind has always struggled with the same set of problems, it seems; accepting mediocrity for safety, fighting mediocrity for growth, and constantly experimenting with questions that generate understanding of the world around them.

These discussions will go on forever, but it’s easy to discuss them and leave it at that.

True understanding comes from experiencing the unknown and figuring out ways to ask better questions. As we were discussing these, an opportunity showed itself, as if it was preordained to happen.

The Motorcycle Problem

Dhanaj left his Honda CBZ Extreme motorcycle at Michael’s place. A fairly well-ridden machine, but it had developed a starting trouble lately, and we couldn’t figure out why.

By the time our technology discussions reached their peak, the bike decided to give up completely. No more kick starts or running starts to the rescue. So we decided to take up the challenge and bring the bike back to life.

Applying the lessons from Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, we decided to use scientific method to solve the bike problem.

The thing is, everyone kind of follows it but stops at the hypothesis stage and leaves it there.

Oh, I forgot to mention—here’s how a scientific method works. Nothing fancy, just a logical process to reach a conclusion.

Anyone who finds anything out of the ordinary has just made an observation and questions why it happened. If their initial assumption (hypothesis) makes them feel nothing out of the ordinary, the case is closed and they go on with their lives. This is normal and crucial for sanity.

Notice there is a question that leads to the hypothesis? The quality of this question either leads to action, i.e., the ‘quest’ for knowledge, or back to the status quo.

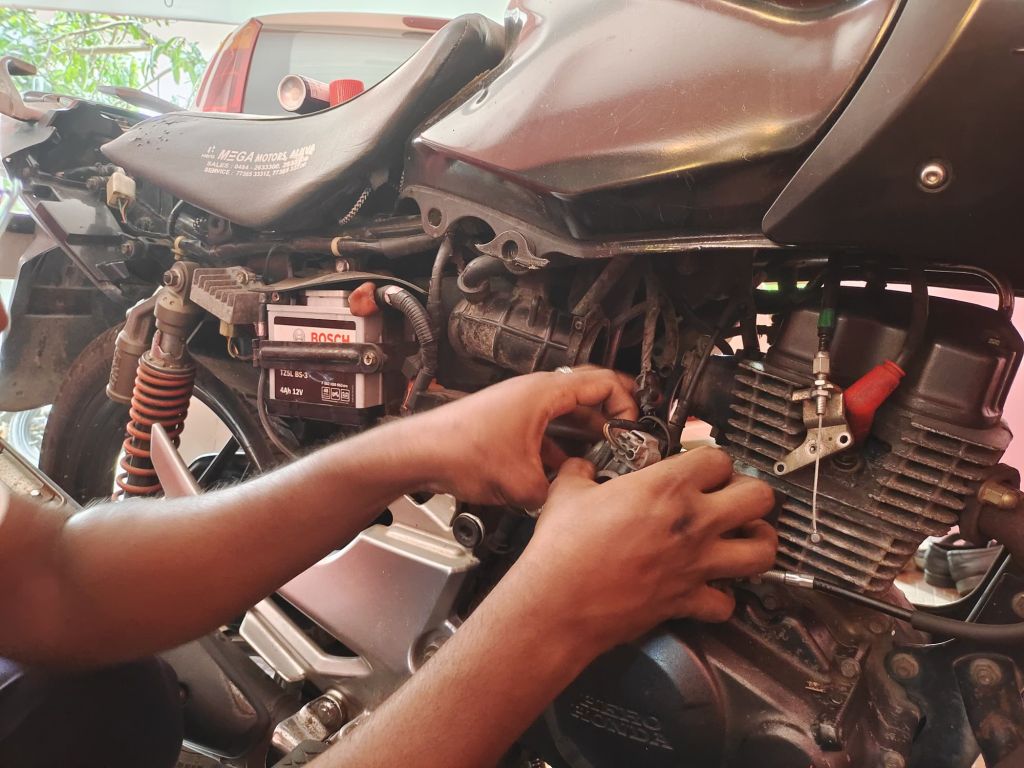

Coming back to our motorcycle problem. We decided to check all the basics for our first hypothesis.

The battery was good, considering the headlights worked well. The starter was also good, with no sounds out of the ordinary. No faulty cables, wiring, or anything obviously wrong.

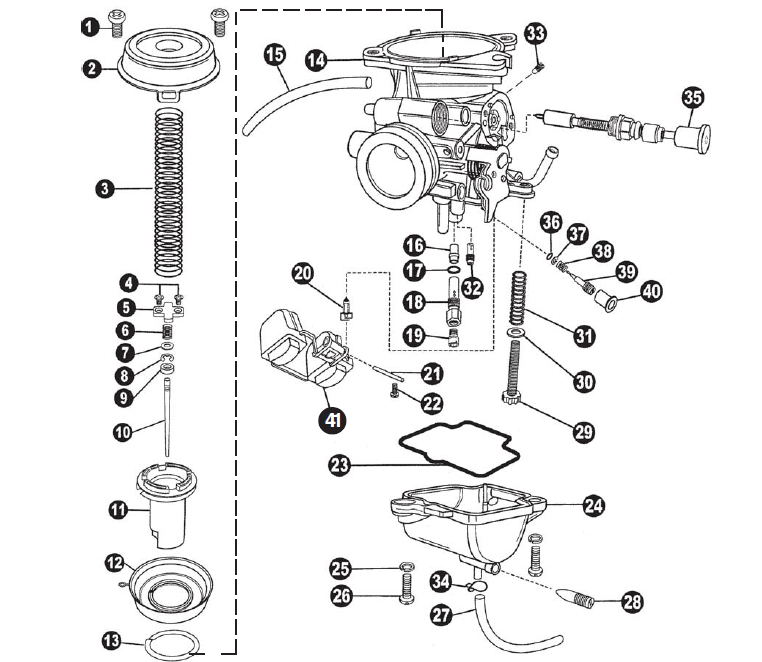

Our next logical culprits were the air filter and the carburetor. While we couldn’t open the airbox with our screwdrivers, we didn’t think it could be the problem and went straight to examine the carburetor.

See how we simply assumed it couldn’t be the air filter? Don’t assume.

We checked the carburetor and found out that fuel wasn’t really going into it but was stuck somewhere along the way.

Thus began our first and crucial hypothesis for the machine repair—the carburetor is clogged, leading to unavailability of fuel to burn, resulting in engine shutoff.

Novelty by Observation

Until then, the motorcycle was a means to an end. A machine that can take us from point A to point B if you are moderately skilled in balancing the machine. Every rider is familiar with its functions: the brake, accelerator, clutch, gear, and the buttons that come with it.

For a normal person, a motorcycle and a horse aren’t too different considering the underlying use they have for the rider. And that’s fair too, as people don’t have to constantly think of any machine as a sum of the subsystems that it’s made out of.

The difficulty arises when the machine stops to perform its intended function. Now form somehow becomes important, which up until now was an afterthought.

I’m sure everyone who has ridden a motorcycle knows about the existence of a suspension system, an engine, and a frame on which everything is mounted.

But when the engine decides to stop working, our first response is almost always a sense of disappointment.

We expected it to work, or at least start, by using the methods used to start the machine earlier. Two or three tries later, a slight fear creeps in to indicate this may not be something you can solve.

Within 10 minutes of trying to start the motor, helplessness enters the scene, telling you that it’s the job of a technician to fix it for you.

Replace the engine with AI, and nothing changes. It’s all the same.

If you don’t instinctively reach out to your trusted technician, you are now presented with an opportunity to observe the problem. Something out of the ordinary that begs your attention. Suddenly you are talking to your motorcycle in a way you never thought of before.

You begin to observe the machine more closely, perhaps the sound it makes, any unusual smells, or leakage to parts you never noticed before. I’ve seen people make quick remarks and accept them to be the truth, laying the topic to rest.

If you’re not that guy, an opportunity has just opened up to see the machine up close.

The machine is no longer alien; it’s getting familiar. There’s a newfound appreciation for the devices on the machine, and you now realize what you bought was more than what you thought.

Experience Trumps Ignorance

We’ve taken the carburetor off the bike after carefully deciding the best mode of operation from YouTube tutorials. The first step is to clean it.

The carburetor we had was fairly old and blackened, so loads of petrol and WD40 spray were sacrificed to get back the shine of the carburetor body.

This heart-sized device is our focus of attention now. A week ago, nobody cared for its existence, but now, it’s a fascinating piece of technology to behold.

We went all in to learn its underlying technology, how the venturi worked like a straw sucking in air, and how the spray of fuel could be controlled.

More than fixing it, our focus was to fully appreciate the device, which we probably won’t unplug once the issue is resolved. The screws, tiny nozzles, and channels where air and fuel moved.

We still don’t know their nomenclature, but we know what each screw does and how delicately they must be placed to run the engine.

Since some of the jet screws looked dated, we decided to buy a carburetor repair kit, which was a collection of springs, jets, and screws, to replace the existing ones. I made an assumption that if I know the year and make of the bike, I’ll be able to acquire similar spare parts.

I brought a change of screws and springs for the carburetor that looked similar but was a couple of millimeters off from the ones we had. Result: the whole kit was useless.

Our learning: figure out the right questions to ask before making a decision.

Outcome and Learnings

Short answer: we couldn’t fix the carburetor.

Long answer: We learned a lot more than just fixing bikes. Experiential learning, uncovering opportunities by improving the quality of our questions, accepting that the solution is not what we were here for, and much more.

Here are our assumptions and learnings while fixing the bike:

- I thought the bike had fuel injection. It didn’t.

- Michael thought the bike had a kick starter. It didn’t.

- We thought we’d work on the bike every day. We couldn’t.

- We’ll find time at least every week to work. Nope.

- YouTube videos can teach you everything. Again, nope.

- Our tools were enough. We were so screwed believing that.

Our biggest learning was that the process of getting the bike fixed should never be rushed. We analyzed our thinking, went back and forth on service manuals, and Michael even found cleaning the carburetor to be a calming experience.

The bike didn’t start even after refitting the cleaned carburetor. And we’ll be pushing the bike to the nearest workshop soon, but we’ll be happy doing it. (That’s a whole other story!)

Finally, the fear of the machine has gone from the both of us. We aren’t experts on bikes, but we know it’s made of parts that can be fixed.

The bike (the problem) has ceased to be a challenge, but more like a marvel of human innovation. I remember Michael’s dad appreciating the carburetor at one point, sharing a moment of joy thinking of the precision craftmaship of the device. These are moments that make machines approachable.

Additional learning: Finding likeminded people to go on learning adventures is incredibly helpful for growth. Always strive to find people or circles that promote curiosity.

Next time anything feels like rocket science, let’s think of better questions.

Book reference: Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, by Robert M. Pirsig

Leave a comment